A blog post by Sarah Pyke

“Living opposite the library saved me”, Carol tells me in our first interview, “completely saved me.” A clever, working-class girl growing up in 1960s South London, Carol read partly to escape an unhappy home life: “I read my way out of insanity […] to keep it together really.” As a child, she visited the library “literally every day.” For Jo, the library was a place of “comfort”: it had “a carpet. Colours. Comfy chairs” as well as “lots and lots and lots and lots of books.” Amy remembers the mobile library van that visited her rural Scottish primary school in the mid-to-late 1980s and early nineties. “That van had a lot of promise,” she explains. “It was very exciting […] Like, what can I find in here?” [1].

Carol and Amy identify as lesbians, and have done since young adulthood; Jo is a bisexual transwoman in her mid-sixties who came out in late middle age. Their recollections are just three examples from the oral histories of books and reading I’ve gathered from self-identified LGBTQ adults, in which the library figures as a crucial site of refuge, exploration, self-definition – even salvation.

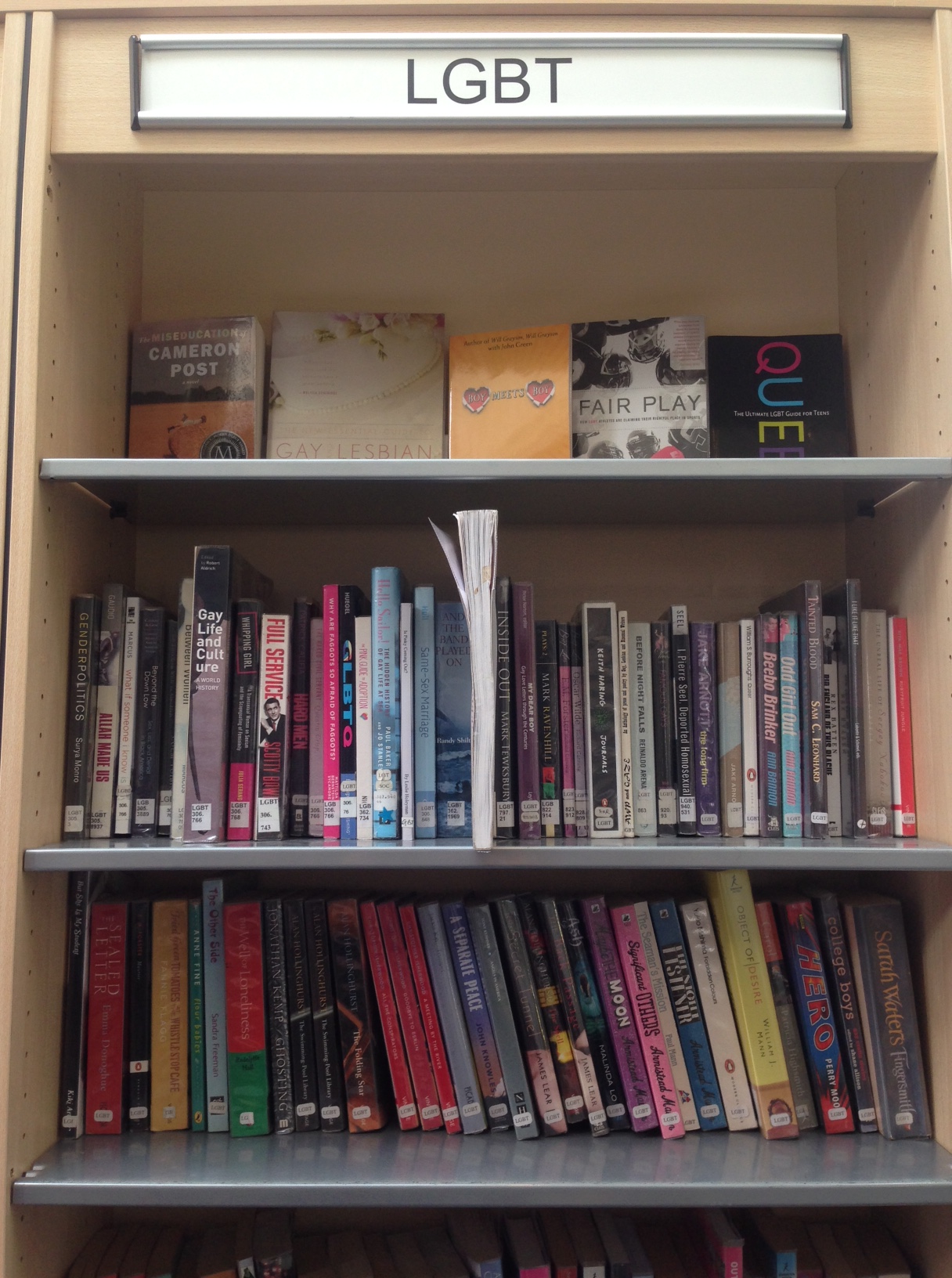

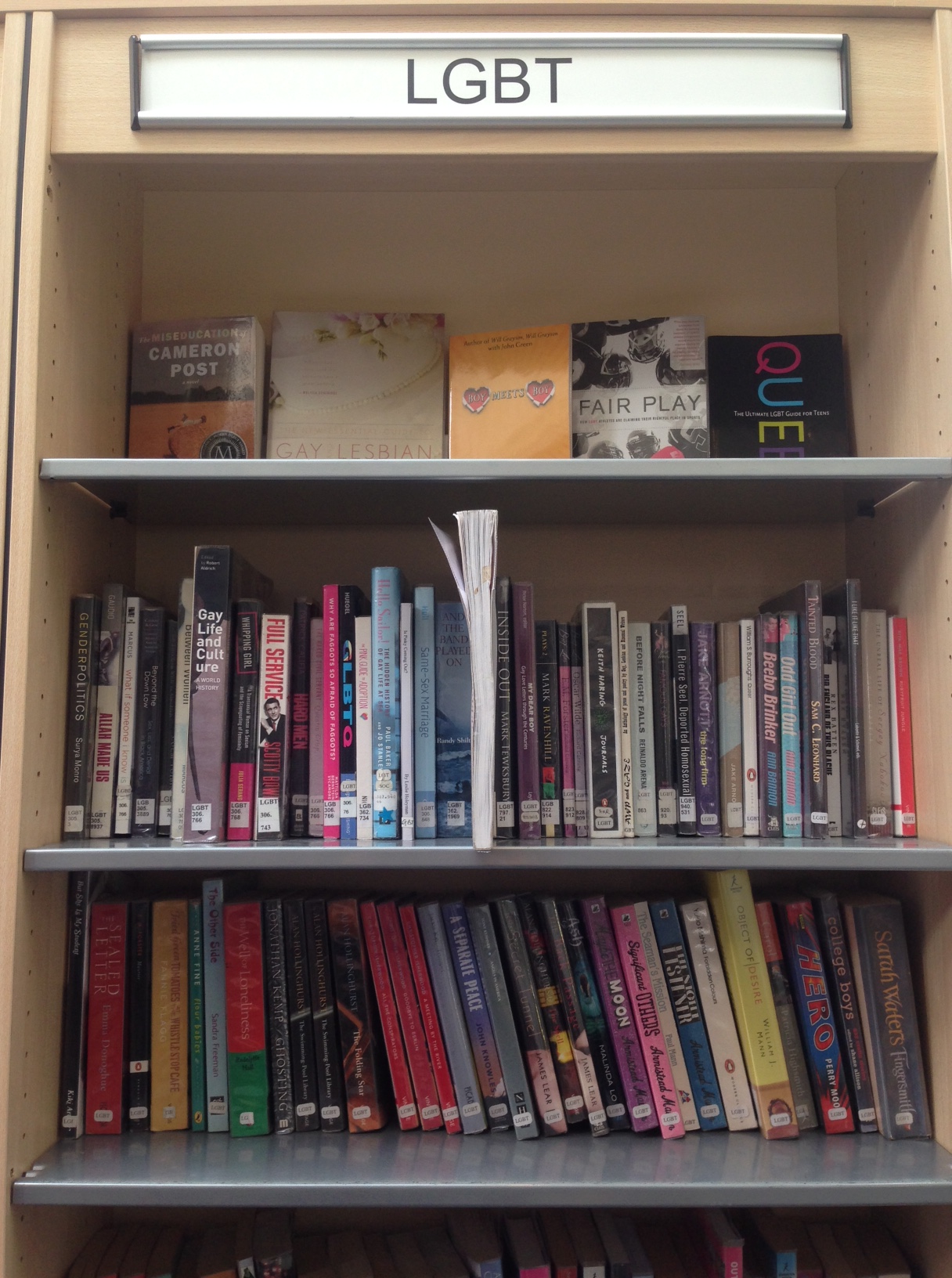

LGBT section, Dulwich Library, 2017. Image credit: Sarah Pyke.

The library has historically fostered specific pleasures – and frustrations – for the LGBTQ reader. On first hearing “lesbian” as a teenager in 1945, Sandy Kern “ran to the library … and looked up the word lesbian and I felt so proud of myself” [2]. Some sixty years later, I circled two small shelves in my local library, then carefully labelled “Lesbian and Gay”. Eventually, I plucked up the courage to pick up a book, then to take one out. For the curious and questioning, those bent on carrying out what Doris Lunden refers to in another oral historical account as “the research that I think has been done by so many lesbians throughout history”, the library is a vital portal [3].

The “comfort” of the library can also be derived from its rules and systems, an ordering of the otherwise chaotic or unstable. Another of my narrators, Mary – a gay woman in her mid-forties – recalls her bafflement, on the cusp of adolescence, “standing in front of the adult shelves, going how do you decide what to read? How do you negotiate it?” At a similar age, Carol, like the teenage protagonist in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985), “started at the As and worked my way through.”

Yet for my narrators, and for other LGBTQ readers, this negotiation of the “adult shelves” can be a particularly delicate or risky business. Looking up “homosexuality” in the dictionary for the first time, Vince Mancino, interviewed by Kath Weston, “took the book and brought it into my room and I hid the dictionary”. For Mancino, there is something dangerously revealing about the circulation of the term “homosexuality” in print; “it was as if”, he says, “I had been found out […] as if I had always known the definition; now I knew the term” [4].

Not only are issues of sexual self-definition and textual definition often bound together, but reading is inescapably a social act. To read – particularly in a public library, subject to the scrutiny of others – is also to be read. “Friends of mine from an earlier generation who were interested in investigating sexuality and sexual identity”, commented Johanna Drucker during the AHRC “Books and the Human” debate held at Central Saint Martins, London, in December 2015, “were timid about going to the section of the library where the books were stored on the shelf.” For the LGBTQ reader, the relations between books and bodies, both so often socially and culturally circumscribed, can be peculiarly charged.

After watching a TV adaptation of Quentin Crisp’s 1968 memoir The Naked Civil Servant aired in the mid-1970s and experiencing “really strange feelings”, Tony, interviewed for the Hall-Carpenter archive of gay and lesbian life stories, “had to read that book. It became an obsession.” Locating it in his local library, however, he “found that it was on the reserved stock list. So it became impossible to get out […] Because it meant I would have to ask for it”. For Tony, his sexuality was – quite literally – unspeakable. “In the end”, he explains, he “wrote a little note to the librarian” and passed it, in silence, across the counter.

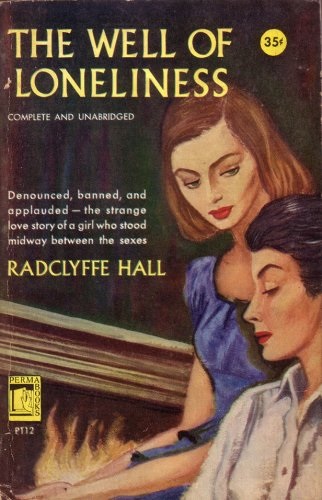

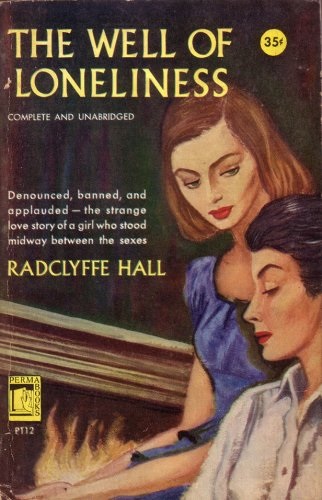

To read Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928) as a teenager in 1950s America, “you had to go to the locked room in the college library and explain why you wanted it”, says science fiction writer Joanna Russ – “a requirement”, she points out, “that effectively prevented me from getting within a mile of it” [5]. Kath Weston recalls her own “raid on the college library” during which she “uncovered” a copy of Violette Leduc’s 1966 “boarding school romance” Therese et Isabelle. “Hands shaking”, Weston checked out the book with “a borrowed library card” [6].

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (Permabooks, 1951), via Wikimedia Commons.

A few years after his hesitant encounter with Crisp’s memoir, Tony also turned his attention to Hall’s notorious novel. Once again, the book was on the reserved stock list, but this time he requested it without embarrassment. “It had last been taken out in 1953. This is in a local library, in Salford,” he explains. “And, I mean, I’m talking now about 1983 or ‘84, so it’s thirty years since anybody had ever had The Well of Loneliness, from that particular library.” Brought into suggestive conjunction with the body of the reader, Tony’s phrasing invites a consideration of the book as an object to be touched and held.

Andy, a gay man in his fifties, remembers during a conversation with me “the yellowed pages and the smell of library books and where I was when I read them”; these are tactile, sensory objects, invitingly material things of paper, ink and glue. While Tony conjures the last imagined reader who “had” The Well of Loneliness, “some lesbian who lived in Swinton in the fifties”, for Andy too, libraries create moments of community and connection with other bodies, other readers: “going into [the library] and getting [the book] and reading it, and knowing other people had read it, and being able to look at the date stamps and see approximately when they’d read it.” These are the “intimacies”, as Leah Price observes, established “even between strangers who handle the same piece of paper, unbeknownst to one another” [7].

“When the book was put back,” Tony continues, “they put it back on the shelves, not in the reserved stock list.” The new positioning of Hall’s novel is both a significant political act in its own right, and a metaphor for Tony’s own ‘coming out’, as the object of the book and the subject of the reader overlap and mesh. In, as he triumphantly puts it, “liberating Radclyffe Hall” – making the book visible, accessible and public, bringing it out of the ‘closet’ of the reserved stock list and onto the general shelves – Tony reflects his own increased confidence in living openly as a gay man.

In carrying out this research, it’s becoming increasingly clear to me that libraries hold stories which proliferate beyond the classified and shelved: stories of confusion, fear and shame, yes, but also stories of connection, community, resistance, affirmation, recognition. For every locked room, reserved stock list or borrowed library card, there are those committed to upholding the library as a democratic, free, civic space – the “heroic librarians” recalled by poet Sophie Mayer in Ali Smith’s Public Library and Other Stories (2015), who displayed work by queer authors in the “small suburban library” of her childhood “even after the passage of Section 28” [8].

Oral histories provide a unique opportunity for these stories – many of which may otherwise have remained untold – to be heard, and, importantly, to be amplified to policy-makers and politicians. In the current climate of austerity, perhaps listening to, sharing and preserving what library users have to say is more necessary than ever. Silence in the library is one thing, but as the UK’s public libraries continue to be subject to punishing funding cuts, staff layoffs and local branch closures, we must not remain silent about them.

Sarah Pyke

Notes

[1] Quotations from Carol, Jo, Amy, Mary and Andy are taken from oral history interviews I carried out with them during 2015, as the PhD researcher on the Memories of Fiction project.

[2] Sandy Kern, in The Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader, ed. Joan Nestle, (Boston, MA: Alyson Publications, 1992), p. 56

[3] Elly Bulkin, “An old dyke’s tale: An interview with Doris Lunden” in The Persistent Desire: A Femme-Butch Reader, ed. Joan Nestle, (Boston, MA: Alyson Publications, 1992), p. 110

[4] Kath Weston, “Get Thee to a Big City: Sexual Imaginary and the Great Gay Migration.” GLQ, vol. 2, no. 3, 1995, p. 258

[5] Joanna Russ, “Introduction,” in Uranian Worlds: a reader’s guide to alternative sexuality in science fiction and fantasy, ed. Eric Garber and Lyn Paleo, (Boston, MA: Hall, 1990), pp. xxxiii–iv

[6] Kath Weston, “Get Thee to a Big City: Sexual Imaginary and the Great Gay Migration.” GLQ, vol. 2, no. 3, 1995, p. 259

[7] Leah Price, How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2012), p. 12-13

[8] Ali Smith, Public Library and Other Stories, (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2015), pp. 75-6

The project’s research informed the production through the interviews, and also through key themes, including the importance of reading and libraries in peoples’ lives (also reflected for example in a

The project’s research informed the production through the interviews, and also through key themes, including the importance of reading and libraries in peoples’ lives (also reflected for example in a

It’s being produced by an experienced and inspiring producer and director, Laura Bridges, and will be part of the theatre’s storytelling festival. As an old library, the Omnibus Theatre is the perfect space for it! More information will become available as the project develops, but for now if you’re interested please take a note in your diaries: 9-12 May 2018.

It’s being produced by an experienced and inspiring producer and director, Laura Bridges, and will be part of the theatre’s storytelling festival. As an old library, the Omnibus Theatre is the perfect space for it! More information will become available as the project develops, but for now if you’re interested please take a note in your diaries: 9-12 May 2018.

At a time of continuing austerity, public libraries are in danger of being perceived by politicians as a luxury. Yet, the social value of libraries and their buttressing of the public good are recurring themes in our research. No matter the groups we worked with, our libraries remain significant in the everyday lives of both the better and the less well off. As community resources in localities as diverse as Roehampton and Putney, public libraries provide space and most importantly the expertise of librarians helping in turn to promote discussion. Readers understand libraries as places where civic society can flourish. Libraries continue to be important in the production of informed citizenship. But libraries are under threat. One final point: the risk from cuts and resulting diminishment is greater to libraries in places such as Roehampton, despite the population’s more obvious need for resource and thirst for reading

At a time of continuing austerity, public libraries are in danger of being perceived by politicians as a luxury. Yet, the social value of libraries and their buttressing of the public good are recurring themes in our research. No matter the groups we worked with, our libraries remain significant in the everyday lives of both the better and the less well off. As community resources in localities as diverse as Roehampton and Putney, public libraries provide space and most importantly the expertise of librarians helping in turn to promote discussion. Readers understand libraries as places where civic society can flourish. Libraries continue to be important in the production of informed citizenship. But libraries are under threat. One final point: the risk from cuts and resulting diminishment is greater to libraries in places such as Roehampton, despite the population’s more obvious need for resource and thirst for reading